The Revolution Against Shady Landlords Has Begun

Vivian Thomas Smith loved her apartment. For nearly three decades, she and her husband, Bradley, had lived in a modest one-bedroom at 2420 Morris Avenue, just two blocks from the raucous beauty of the Grand Concourse in the Bronx. The brick apartment complex was a co-op where some families, like theirs, still rented. Vivian, 71, was a retired secretary who had worked for decades at Montefiore Medical Center. Bradley, 81, had also been employed by Montefiore, doing maintenance work before his retirement. Vivian watched her neighbors’ kids grow up. When her own son got sick, her friend down the hall helped nurse him through the long illness that preceded his death. Vivian may have worried about the increasing crime in her neighborhood, but when she walked through her building’s beautifully tiled lobby, she felt secure that she and Bradley would stay there for the rest of their lives.

That all changed in November 2020, when the private equity firm Glacier Equities bought all the rental units in her building. Just over a year later, on December 1, 2021, the Smiths got a letter offering them an ultimatum: buy your apartment or leave when the lease expired on March 31, 2022. “Out of the clear blue sky. No reason, nothing. For 27 years we were never late on rent, never missed a month,” Vivian said.

The couple wanted to buy, but bills from their son’s illness had wrecked their credit. No bank would give them a mortgage. At the same time, their economic situation made finding a new rental almost impossible. Because of the small pensions they received in addition to their Social Security, they made too much money to qualify for subsidized housing. Yet they made nowhere near enough to rent a new apartment.

“We spoke to housing lawyers. The first one said ‘cause our apartment was not rent-stabilized, ‘You don’t have a choice. You have to leave,’” Vivian said.

Throwing an elderly couple out on the street might be monstrous, but it’s perfectly legal in New York State. If, like the Smiths, you are a tenant in one of the state’s 1.6 million market-rate apartments, your landlord can get rid of you at the end of your lease—no reason necessary—by means of what’s called a holdover eviction. And landlords do it all the time. The more than 32,000 holdover eviction cases brought before New York State housing courts in 2022 represent a small sliver of the problem; unable to afford the stress and financial costs of a legal battle, many tenants just pack up and leave.

A bill that had been making its way through the state Legislature for several years could have been a life raft for the Smiths. Backed by a coalition of housing organizations, the legislation—dubbed the Good Cause Eviction bill—required most landlords to offer lease renewals to tenants like the Smiths, who had paid their rent on time and stuck by the terms of their leases. It also limited rent increases to prevent landlords from forcing people out by raising their rent hundreds of dollars a month.

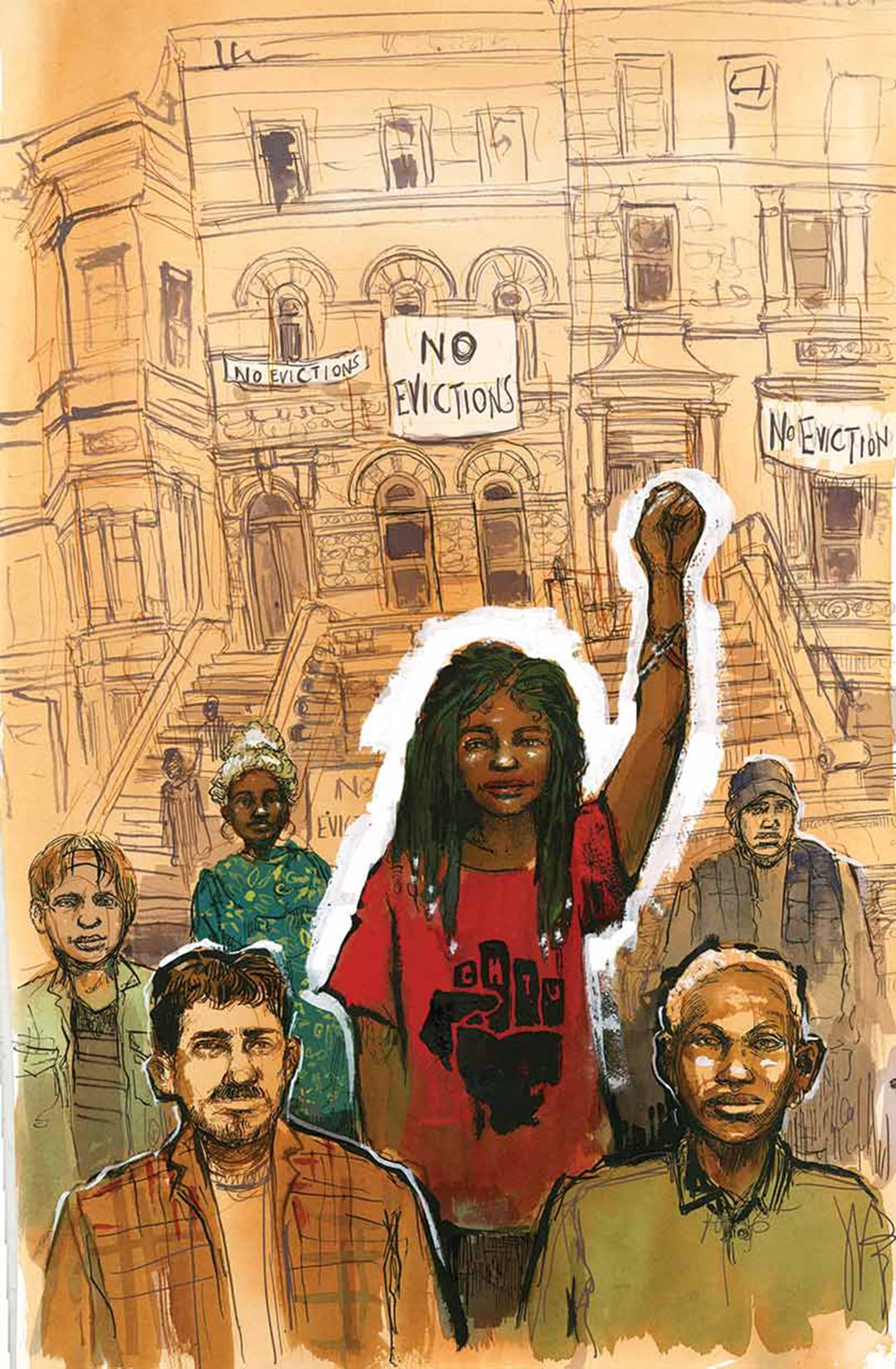

This bill could have saved the Smiths, and countless other New Yorkers, from eviction. But despite loud, passionate, and relentless campaigning by housing activists and tenants—including Vivian Thomas Smith—lawmakers refused for years to even put Good Cause legislation up for a vote. The Smiths, and all the other tenants like them, were on their own.

The story might have ended there, in defeat. But movements are stubborn creatures. If people fight long enough, they learn that losses are temporary and that victory can only come through a refusal to retreat. Last December, just a month after Democrats held their statewide majority in the midterms, the tenants’ rights group Housing Justice for All renewed its Good Cause campaign and then went even bigger, unveiling “Our Homes, Our Power,” a package of five bills intended to address the worst housing and homelessness crisis in decades. All of the proposals are important, but Good Cause remains the most crucial—not only because it has the power to save people right now, in the present, by slowing the constant stream of evictions, but also because it’s the only one that fundamentally reshapes the relationship between landlord and tenant. Housing activists have until June 8 to persuade state legislators to stand up to the real estate industry and protect their constituents.

New York City is brutal to renters. As of 2017, half of us spent a third of our income on rent; a third of us spent more than half. The competition for an affordable place is harrowing, with the vacancy rate for apartments that rent for under $1,500 a month hovering at less than 1 percent. Many of us pay nonrefundable application fees just to get our foot in the door, followed by thousands of dollars to the landlord’s broker, and often thousands of dollars more in glorified bribes to the landlords themselves. If we are lucky enough to score a place, it had better be rent-stabilized (a rare prize when landlords are pulling tens of thousands of rent-stabilized units out of circulation every year) if we want to stay. A lease on a market-rate apartment gets us only 12 months of stability. After that, we’re vulnerable to whatever unconscionable rent increases the landlord feels like imposing, or we are back on the apartment hunt—or, for many low-income people, the street—again.

Ideally, this collective precarity should unite people. As Anh-Thu Nguyen, a labor and tenant organizer in Brooklyn, told me, “I don’t care if you’re some bro in the West Village paying $5,000 a month, or a little old lady in Spanish Harlem in a rent-stabilized place for 30 years. You represent a class. That class is the landless…. You want stability, a place you can call home.”

Instead, communities often wind up pitted against each other. One group is forever being forced out, then pushed into areas where another group, often poorer, is being forced out too. This gentrification gets blamed on tenants, even though landlords are the ones raising the rents. When a landlord evicts an abuela and rents her apartment to an NYU grad student, politicians point to gentrifiers or transplants, not the landlord, as the problem. They seldom mention that there was an actual bill that could have kept the abuela in her home.

This is not just theoretical. Good Cause Eviction has long been the law in New Jersey, where cities like Trenton and Jersey City have some of the lowest eviction rates in the country. It also exists in cities like Montreal, as well as in Japan.

Good Cause was first proposed in 2018 by a collection of tenant groups in New York State that was then called the Upstate Downstate Alliance (it eventually became known as Housing Justice for All). In 2019, it found a legislative champion when democratic socialist Julia Salazar came to the state Senate.

One of Salazar’s first acts was to write the Good Cause Eviction bill. The bill was then folded into a major package of housing reforms, including legislation that makes it much harder for landlords to kick out rent-stabilized tenants by renovating buildings in order to raise rents and prevents them from taking apartments out of stabilization once the rent reaches a certain threshold. While those reforms were passed into law, the party leadership refused to bring Good Cause up for a vote. This was largely due to the resistance of the real estate lobby, which found Good Cause threatening precisely because it diminishes some of landlords’ unchecked power.

The next year, Covid hit, and over 330,000 people fled New York City—mainly from the richest zip codes. Many of them moved upstate in search of a slice of virus-free paradise, driving up rents and home prices in those spots as they went. Back in the city, some landlords panicked in the face of the exodus and offered previously unthinkable rent reductions to entice tenants to stay. Others, especially if they owned rent-stabilized apartments, warehoused their empty units and bided their time.

By April 2020, more than 16 percent of the state’s population was out of work. For hundreds of thousands of tenants, making rent became impossible. If they didn’t pay, what then? Would the courts really send sheriffs to chuck their possessions out onto the sidewalk, then shuttle them to crowded homeless shelters?

A movement erupted to cancel the unpayable rents—led by both established tenant groups and young people radicalized in the uprising that emerged after George Floyd’s murder. Banners were dropped from bridges. Raucous protests were held outside the homes of recalcitrant politicians. It made only a modest impression. While the state and federal governments did act, declaring moratoriums on evictions starting with the CARES Act in March 2020, they wouldn’t cancel rents. Bills still came due each month, and the debts metastasized. Two years later, 595,000 New York City renters were still behind—and landlords were anxious to get them out.

With the arrival of the Covid vaccine, the bars reopened, restaurants buzzed, and the rich flooded back to the city like some revanchist army. For landlords, these returnees were more enticing than those of us who stayed, whether or not we owed back rent.

The federal moratorium expired in October 2021 and the state moratorium in January 2022. Immediately, the evictions began.

The pandemic was a bonanza for institutional investors in residential real estate. The most famous villain is BlackRock, the multinational investment behemoth, but Glacier Equities has also done a number on New York City. Glacier is a real estate private equity firm, or REPE. A REPE raises cash from private investors to buy a property—say, an apartment building. The REPE then tries to get tenants out, often neglecting the building or hiking rents. Finally, the REPE sells the building, gobbling up the profits for its investors and itself. Over the past two decades, Glacier has flipped—or as it says on its website, “acquired, developed, and sold”—2,200 condos and co-ops in and around New York City. During the first year of the pandemic, it snapped up 255 units in Bronx and Manhattan co-ops. The Smiths’ apartment was one of them.